|

King Charles III wore a kilt for his first public engagement in Scotland after Queen Elizabeth II’s death, yet current western society hasn’t whole-heartedly embraced men wearing kilts, or other skirt-like garments. Today, women enjoy most of the advantages of men’s attire. However, men’s fashion is still subject to the tyranny of trousers, and there remains a taboo surrounding men in skirts. Trousers were forged in the crucible of two revolutions – the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution. Extravagance in dress was considered one of the most tangible expressions of the French aristocracy. French revolutionaries and their sympathizers adopted the typical working-class dress for men in the 18th century – loose baggy trousers and jackets. Their slogan, “Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood”, found its outward manifestation in the clothing of the revolutionaries and their sympathizers. Advocating for the reform of French dress was an outward sign of a concern for democracy and equality. The Industrial Revolution factory system of mass production and the often-dangerous work gave rise to functional clothes that lessened the possibility of injury from clothing getting caught in machinery. Loose fitting garments yielded to the practical need for safety in the mechanized world of the Industrial Revolution. The stigma of men in skirts can be traced back to the strict dress codes and gender rules adopted with industrialization. However, men in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East continued to wear traditional garments – kimonos, sarongs, caftans, djellabas. It’s only in the West that skirts, or dresses, are assigned to women alone. Skirts and dresses aren’t demarcated by gender around the world. Fashion designers have often looked to non-Western cultures for sources of both inspiration and legitimization. In historical military garb, the display of male legs was a sign of virility and athleticism mirrored in the dress of Scottish Highland warriors, Roman gladiators and Greek gods. Scottish troops in World War I fought in kilts but they lost their practical credibility by the beginning of World War II. The modern kilt albeit relegated to ceremonial events still evokes a heighten sense of masculinity in the current popular imagination. With King Charles III’s ascent to the British throne, he continues to advocate for training in traditional Scottish skills including tartan textiles at his foundation school https://princes-foundation.org/school-of-traditional-arts in Scotland. One graduate of the tartan textile program is Graeme Bone, a former Scottish construction worker. Mr. Bone has become world-renown for his handsewn Scottish luxury kilts. https://graeme-bone-fashion.square.site. The revolutionary spirit of men in kilts still courses through the fashion world. For 21st century youth and subcultures, the kilt, and skirts, continue to be a means, and a symbol of transgression and self-expression. However, Graeme Bone is just one example of many designers working to popularize men in kilts by taking them off the catwalks of the fashion world and onto the sidewalks of the cities of the world. Who knows when there will be a cultural tipping point where anybody can wear a kilt, or a skirt – where it’s no longer a rebellious act of fashion but an ordinary choice not dictated by cultural constraints. Perhaps, one of King Charles III’s contributions to modernity will be ushering in the age of the kilt, or the skirt, with widespread acceptability regardless of one’s gender. Time will tell. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books:

0 Comments

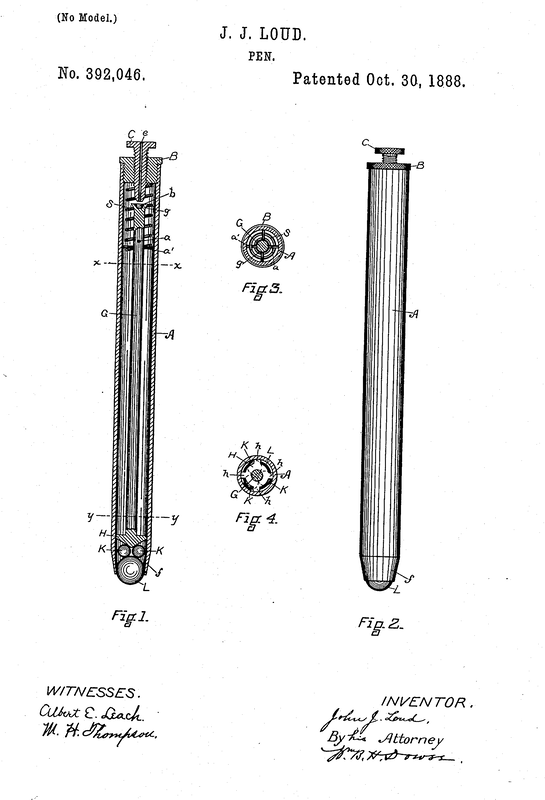

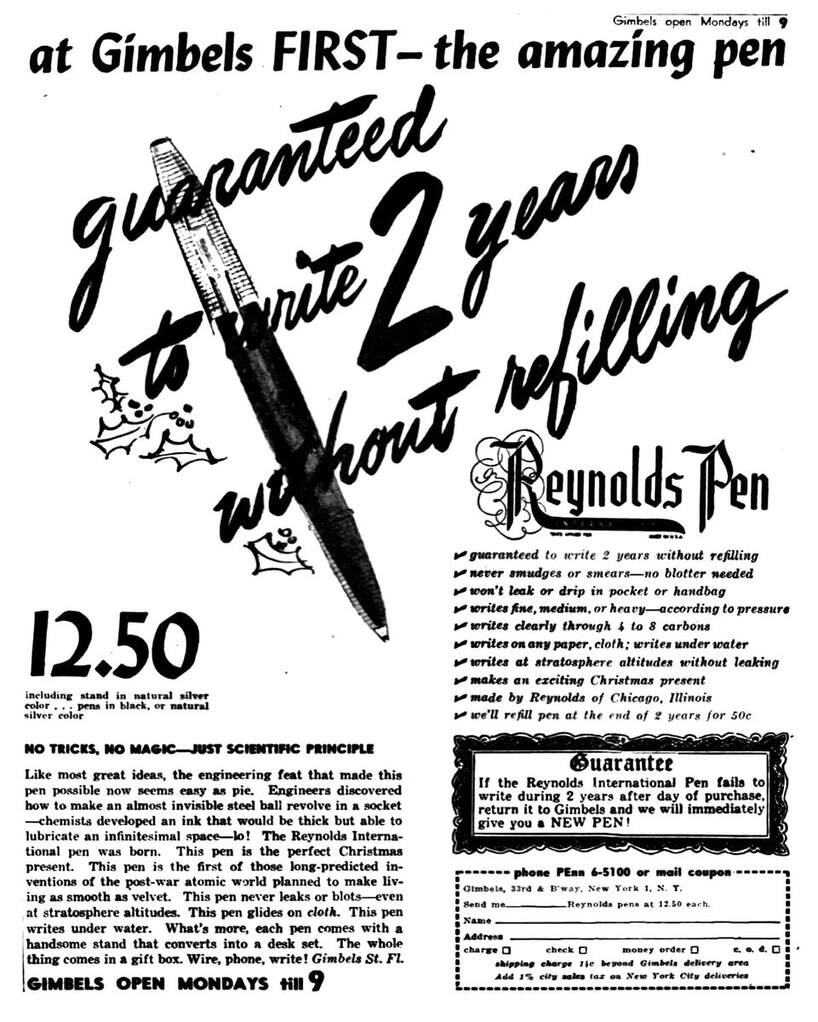

Now that most COVID-19 restrictions have been lifted, people have started travelling again. The robust return to travel brings with it reminders of the many airline rules and regulations that impact the safe and efficient movement of passengers and cargo. The Travel Security Association’s (TSA) liquid restrictions remain unchanged. You’ll need to get out those little 3.4 ounces bottles that you tucked away in the bottom of your suitcase. And airlines continue to impose weight limits and dimensions on our luggage, too. Yet they don’t weigh us. Why is this? I thought I would easily find a chart of specific passenger weight limits based on the physics of gravity and thrust needed to get an airplane off the tarmac, keep it in the sky and land it safely. I discovered though that currently, there isn’t any federal regulation with exact passenger weight limits on an aircraft. However, what I did find was a Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Advisory Circular from May, 2019, which is the closest thing that carries the authority of a regulation. It stressed the importance that airline protocols accurately reflect revised "average passenger weights", and even included an option of weighing passengers at the gate. FAA standard for the average adult passenger and carry-on bag weight to 190 pounds in the summer and 195 pounds in the winter. This FAA advisory demonstrated the need to tweak its standards to reflect more accurately the changes to the average weight of Americans over the last several decades, considering the nation’s widening waistlines. These changes were a result of the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2008 National Health Statistics Report which determined that the mean average weight is now 194.7 pounds for male adults over age 20 and 164.7 pounds for women over the age of 20. Mean average weighs inched up even further between 2015 - 2018 to 199.8 for men and 170.8 for women. I learned that most of an aircraft’s weight is fuel. But that weight is a given. Passenger weight (and luggage), on the other hand, is variable. How might passenger weight impact the world of commercial aviation? Samoa Air, a small island-hopping airline, might provide some insight. It’s the world’s first air carrier to charge passengers by their weight and that of their luggage rather than per seat. American Samoa has one of the highest obesity rates in the world. In the early 2000s, the adult overweight and obesity rate in the territory was nearly universal, at 93 percent, while the rate for children was close to 45 percent. Samoa Air defends its plan as the fairest way to fly in some cases actually ending up cheaper than conventional tickets. It has begun charging passengers by weight. Passengers pay a fixed price per kilogram (2.2 pounds) which varies depending on the route length. The cost is .93 cents to $1.06 per kilogram (2.2 pounds). It seems that for now Samoa Air will continue to be an aviation outlier. Presently, the only other air carriers that actually weigh individual passengers on each flight are the ones operating extremely small aircraft and helicopters which has always been the case. Deceasing airline profitability, skyrocketing fuel costs with increased safety concerns could perhaps one day push the concept of at gate weigh-ins in the future. For now, I suspect weighed averages will prevail since I don’t think passengers will be agreeable to be subjected to yet another indignity at the airport. So are you ready to jump on the scale? Sources: https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_120-27F.pdf https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/body-measurements.htm https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/a-problem-in-paradise/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Samoa Books: Cheap, reliable, and portable; ballpoint pens today are used daily by millions worldwide. But that wasn’t always the case. Fountain pens dominated the marketplace until the aftermath of World War II. The earliest US patent was granted to John J. Loud, an American leather tanner, in 1888. His patent improved the fountain pen’s ability to mark up leather before it was cut, whereas previously pencils were unable to do the job, fountain pens proved too messy. The distinct features of his patent were small rotating metal balls at the base of the pen held in place by a socket, similar to a roll-on deodorant stick. While Loud’s patent did improve the fountain pen’s ability to mark on rough surfaces, it was too rough to use on paper, and didn’t address the ink leakage and smudges. The patent solved his particular problem while working with leather, but its use was limited, and the patent eventually lapsed. Then in the late 1920s, Laszlo Jozsef Biro, a Hungarian newspaper editor whose own frustration with fountain pens led him along with his brother, Gyorgy, a dentist and chemist, to design a new writing instrument based on John J. Loud’s 1888 patent. The key to their success was a new, thicker ink which dried quickly and smaller metal balls at the pen tip. Their modern-day ballpoint pen premiered at the 1931 Budapest International Fair. Its prospects were moved forward by a chance encounter while Laszlo Biro was on vacation, where it met with the approval of a fellow vacationer, Agustin Justo, the then Argentinian president. Justo invited the Biro brothers to set up a plant in his country. Initially, they declined. However, as Jews, the gathering clouds of the European war in 1939 made them reconsider Justo’s offer. In 1941, the Biros’ brother emigrated to Argentina. There, they and their friend, Juan Jorge Meyne, filed for a patent and started Biro Pens of Argentina. Birome was the name given to their pen, a combination of Biro and Meyne names. It debuted in 1943. In Argentina, the trio met Henry Martin, an English accountant, who thought the pen would be of interest to the British Air Ministry. He knew that at high altitudes the ordinary nib-type fountain pen tended to leak due to pressure changes and was unsuitable for Royal Air Force air crews who had to make up their logs while in flight. The British didn’t immediately take Martin’s suggestion. Eventually, though, 30,000 pens were manufactured in England by Miles Aircraft for the R.A.F (Royal Air Force). The ballpoint pen’s popularity didn’t spread to North America until 1945. Two companies spent $500,000 to license it for the US market, but they were beaten to the punch by a savvy American businessman, Milton Reynolds. While visiting Argentina, he bought some Biromes, returned to the US, immediately set up the Reynolds International Pen Company, then tweaked the Biro patent. Within four months, he began selling them. He called it "Reynolds Rocket". It was heavily marketed with the promise that it would only need refilling every two years. It debuted in October, 1945 at Gimbels Department store in New York City. It was an immediate success. Priced at $12.50/ea ($199.66 in 2022 $$), Gimbels ordered 50,000 units and sold 30,000 by the end of the first week. In the rush to market it, Reynolds gave priority to the promotional aspects of the pen and blatantly ignored flaws in the pen functionality. Consumers soon became disenchanted with the ballpoint pen which didn’t live up to the hype. Many returned to fountain pens. In 1954, Parker Pens introduced its first ballpoint pen, the “Jotter”. It wrote five times longer than the “Rocket”, had multiple tip sizes, and large-capacity ink refills. It worked and the public embraced it. Parker sold 3.5 million Jotters at prices that ranged from $2.95/ea ($31.71 2022 $$) to $8.75/ea ($94.04 2022 $$) in less than a year. Then along came Marcel Bich, an Italian-born French industrialist who created a new French company, Societe Bic. He dropped the “h” in his name and began selling pens called BICs in 1950, mass producing them at low cost. It was a revolutionary turn in the evolution of the ballpoint pen. In 1958 Bich brought the pen to the American market. The Bic pen was soon selling at 29 cents ($2.89 2022 $$) with the slogan "writes the first time, every time!" The BIC pen ushered in the real beginning of the broad use of ballpoint by ordinary people in their daily lives. Its reach over time extended to other areas of life as individuals and organizations began to experiment. The ballpoint pen's portability allowed doodling and sketching to reach new heights and have been used by astronauts in outer space. Ballpoint pens have even proven to be a versatile art medium for professionals known as “ballpoint pen artists”. Explore the work of James Mylne https://www.jamesmylne.co.uk/, Il Lee https://artprojects.com/il-lee/il-lee-ballpoint-pen-on-paper/and Jonathan Brechignac https://bit.ly/3LQZ9fO in this genre. The Museum of Modern Art recognized the Bic Cristal's industrial design by introducing it into the museum's permanent collection https://www.moma.org/collection/works/82141 Ballpoint pens have also made their way to the halls of power in Washington, DC. Presidents sign legislation with pens, and each has had his own favorite brand. President Kennedy preferred a Parker pen; more recent presidents: Bush, Obama, and Biden have favored Cross pens; and Trump used a Sharpie permanent marker. I’m sure you have your own favorite. My current pen of choice is a CVS Caliber Retractable Ball Pen 1.0 mm tip (medium tip), black ink. A four pack costs $5.49 or $1.37 each. What’s yours? Sources: Books:     Websites and Blog Posts:

Rebecca, Maksel. "If you like ballpoint pens, thank the R.A.F. ." , Smithsonian : Air & Space Magazine , 10 June 2015, www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/ballpoint-pens-RAF-180955537/. Accessed 26 May 2022. Dowling, Stephen. "The cheap pen that changed writing forever ." , 29 Oct. 2020, www.bbc.com/future/article/20201028-history-of-the-ballpoint-pen. Accessed 26 May 2022. O, Catherine. "The inventor behind the modern ballpoint pen." , Undated , www.pens.com/blog/the-inventor-behind-the-modern-ballpoint-pen/. Société Bic / BIC Corporate US https://us.bic.com/en_us/about_bic |

Curiosity Corner writer & contributor:Helen Beckert, Reference Librarian at the Glen Ridge Public Library Archives

June 2023

Categories |

|

Glen Ridge Public Library

240 Ridgewood Avenue Glen Ridge, NJ 07028 Phone: 973-748-5482 Email: [email protected] © 2024 Glen Ridge Public Library Site last updated July 15, 2024 |

LIBRARY HOURS Monday 9 am - 8 pm Tuesday 9 am - 8 pm Wednesday 9 am - 8 pm Thursday 9 am - 5 pm Friday 9 am - 5 pm Saturday 9 am - 5 pm Sunday CLOSED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed