|

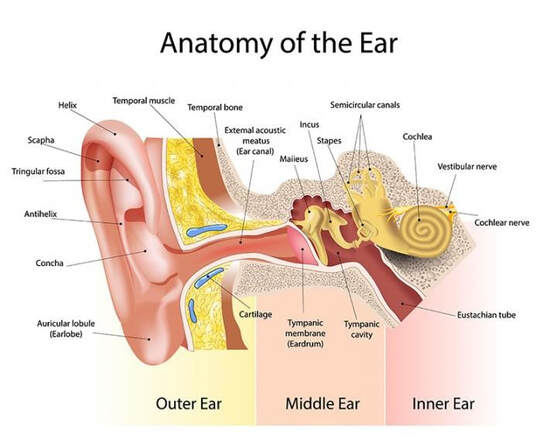

Recently while waiting for a bus, my ears were assaulted simultaneously by the sounds of construction equipment, sirens, car horns and the whiz of traffic. My ears hurt. Yet, when I saw two sparrows pecking on the sidewalk for food, I noticed that they seemed oblivious to all the noise. I thought to myself, “How could such small creatures (a sparrow weighs approximately 0.85 – 1.4 ounces) with ears that are tiny holes on the side of their heads covered with feathers, withstand such a high frequency of noise. I then thought, “Is it possible that these birds are deaf?” I discovered that I’m not the only one intrigued by birds and their hearing. Stanford University scientists are actively studying why birds never go totally deaf yet we humans do. Their research is showing that birds can regrow damaged hair cells in their inner ears - an amazing anatomical feat. So where exactly are these hair cells located and how do they work? First, let's look at the anatomy of the human ear. The ear is made up of three parts: the outer ear, the middle ear and the inner ear. These microscopic hair cells, which birds can regrow, are located in the cochlea of the inner ear. The cochlea is shaped like a small snail and is about the size of a pea. It is fluid-filled and lined with these tiny hairs (there are about 15,000 in the human ear) Vibrations are transmitted as waves from the outer ear to the eardrum. The eardrum passes the vibrations along through three tiny bones, the malleus, incus and stapes. They pass vibrations to the cochlea. The vibrations pass through the cochlea fluid and over the tiny hair cells in a wave-like motion creating electrical signals which are sent to the brain via the via the cochlea nerve. At the end of this process, we are able to hear the sounds created by the initial vibrations from our outer ear. Healthy hair cells can be likened to wheat standing tall in a field. In humans, these tiny hair cells die for various reasons: injuries, aging and loud noises. Dead hair cells look like a wheat field pelted by heavy rain which don’t grow back in humans. Scientists are working to unravel this mystery of how birds can regenerate cochlear hair cells. And the discovery and identification of gene mutations related to cochlea hair cell degeneration, offers another avenue to pursue in their quest to find a way to regenerate healthy hair cells. If, and when they do, it holds out the promise that one day we could be like our feathered friends and never go permanently deaf. I hope this post gives you a renewed appreciation of the sense of hearing, how our ears work and the wonder of birds. Spiro, Ruth. Baby loves the five senses: hearing! Watertown, MA, Charlesbridge, 2019. Sibley, David. Sibley guide to birds. 2nd ed., New York, Knopf, 2014 .

0 Comments

|

Curiosity Corner writer & contributor:Helen Beckert, Reference Librarian at the Glen Ridge Public Library Archives

June 2023

Categories |

|

Glen Ridge Public Library

240 Ridgewood Avenue Glen Ridge, NJ 07028 Phone: 973-748-5482 Email: [email protected] © 2024 Glen Ridge Public Library Site last updated July 15, 2024 |

LIBRARY HOURS Monday 9 am - 8 pm Tuesday 9 am - 8 pm Wednesday 9 am - 8 pm Thursday 9 am - 5 pm Friday 9 am - 5 pm Saturday 9 am - 5 pm Sunday CLOSED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed