|

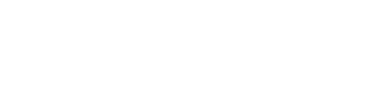

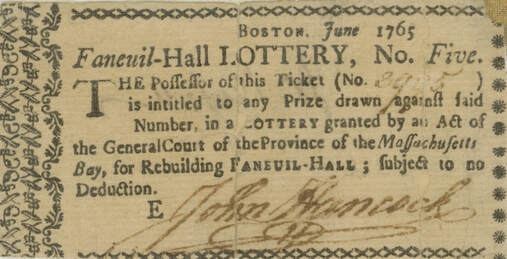

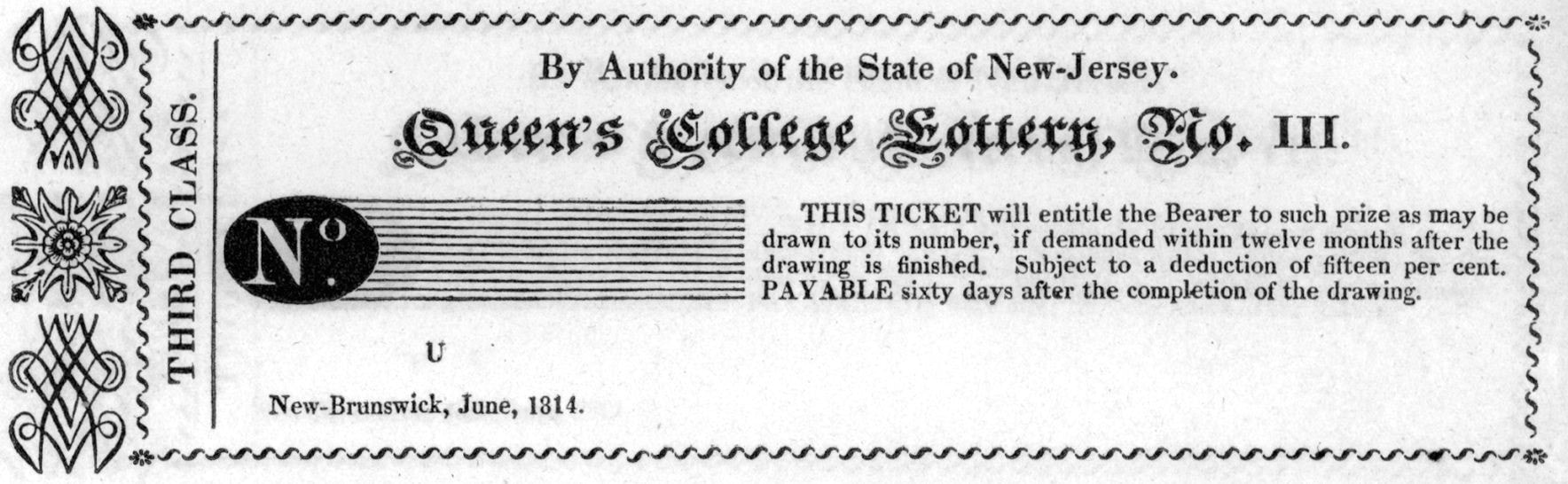

Two New Jersey scratch-off lottery tickets were tucked in a birthday card. I knew I didn’t win but I became intrigued by the concept of lotteries. I discovered they have a long history traceable to ancient times. According to the North American Association of State and Provincial Lotteries (NA, a type of lottery funded the building of the Great Wall in China. In the Old Testament, in the book of Numbers (26: 55 – 56) Moses takes a census of the people of Israel and divides the land among them by lot. Emperors Nero and Augustus had lotteries to give away property and slaves during Roman festivals and holidays. Burgundy and Flanders in the 15th century held some of the first European lotteries. The funds were used for defense or aid to poor. Ventura, considered to be the first European lottery to award monetary prizes, was held in the Italian city-state of Modern in 1476. However, the lottery that came to serve as the model for modern lotteries was the Genoese Lottery named for the game which originated in the Italian city of Genoa in the 17th century. It quickly spread to other Italian cities and elsewhere. Italy’s first national lottery was created in 1863 providing income for the unified Italian nation. In 1566, England’s Queen Elizabeth l needed to raise money for repairing harbors and other public projects. She had two choices: levy a new tax on her citizens or hold a lottery. Elizabeth I established England’s first state lottery. The cost was high, limited pool of 400,000 and included other goods. To sweeten the pot, all participants would be granted immunity from arrest, felonies or treason. The Irish Hospitals’ Sweepstakes, commonly known as the “Irish Sweepstakes” begun in the 1930s was established to fund hospitals. A state lottery replaced it in 1987. The Sydney Opera House in Australia was another large-scale project underwritten with lottery funds. Lotteries found their way to our shores in 1621 to help finance the Jamestown settlement. Then again in 1776 when the Continental Congress established a lottery to raise funds for the American Revolution. Even though that lottery was jettisoned, over time other localized private lotteries were created. One example was the lottery that raised money to rebuild Boston’s Faneuil Hall after a devastating fire in 1761. Proceeds from other public lotteries aided in the building of many colleges. In 1814, the Queen’s College (now Rutgers University) in New Brunswick, NJ was a beneficiary of lottery proceeds. The popularity of lotteries has ebbed and flowed marred by corruption, scandals and shifting public sentiment. Louisiana’s lottery was enormously successful over its 25-year run from 1869 – 1894 in all states. In 1890, President Harrison and the Congress condemned lotteries as “swindling and demoralizing” and prohibited the interstate transportation of lottery tickets. These actions had a chilling effect and Louisiana was the last U.S. state lottery until 1964 when New Hampshire launched its own sweepstakes on March 12, 1964. The New Jersey State Lottery was launched In November, 1969. New Jersey voters overwhelmingly approved a constitutional amendment that called for the establishment of a State Lottery as part of the general election. The 81.5 percent majority in favor of a Lottery was one of the largest in New Jersey political history. On December 16, 1970, the first lottery ticket was sold to Gov. William T. Cahill. Net proceeds of the lottery are constitutionally dedicated to benefit state institutions and state aid for education. The lottery generates approximately $1 billion dollars annually in net proceeds. However, beginning in 2018, the Lottery's net proceeds for a 30-year term will used to bolster New Jersey's critically underfunded public employee pension system for teachers, police and fire personnel and other public employees in conformance through the Lottery Enterprise Contribution Act, P.L. 2017, c.98 passed on July 4, 2017. At the end of this 30-year contribution term, the state pension plans are expected to be 90 percent funded. In year thirty-one, the lottery enterprise reverts back to the state. There are only five US states currently without a state lottery: Alabama, Alaska, Hawaii, Utah and Nevada. The absence of the lottery in Alabama, Hawaii and Utah reflect the potential implications of gambling. However, Alaska’s abundant oil resources provide extra state funds. Nevada sources additional state funding through casino gambling profits. Click on this link for the North American State and Provincial Lotteries (NASPL) to see how the remaining 45 states with lotteries use their lottery net proceeds. Please note that the information on the NASPL website reflects data collected for the fiscal year 2016. https://www.naspl.org/wherethemoneygoes SOURCES: Lewis, Danny. "Queen Elizabeth I held England’s first official lottery 450 years ago." Smithsonian Magazine , 13 Jan. 2016, Accessed 29 https://bit.ly/3NtWJWR Mar. 2022. Herman, Robert D. and Glimne, Dan. "lottery". Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Mar. 2013, https://www.britannica.com/topic/lottery. Accessed 29 March 2022. "Interesting facts about the Sydney Opera House 15 pieces of useful trivia about the beloved building." Sydney Opera House , www.sydneyoperahouse.com/our-story/sydney-opera-house-facts.html. Accessed 29 Mar. 2022. "History: giving dreams a chance since 1970." New Jersey State Lottery , www.njlottery.com/en-us/aboutus/history.html. Accessed 29 Mar. 2022. Petrecca, Steven M. "The Lottery Enterprise Contribution Act - Why it is important ." New Jersey Department of the Treasury, The Bond Buyer , 25 July 2017, https://bit.ly/3qIOLiL. Accessed 29 Mar. 2022. LegiScan, legiscan.com/NJ/S3312/2016. Accessed 29 Mar 2022 "Where does the money go?" North American Association of State and Provincial Lotteries, www.naspl.org/wherethemoneygoes/. Accessed 29 Mar. 2022.

0 Comments

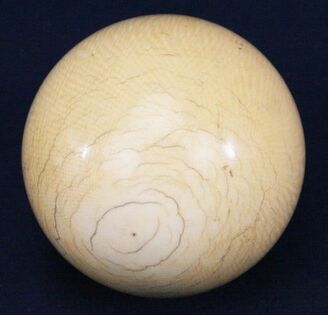

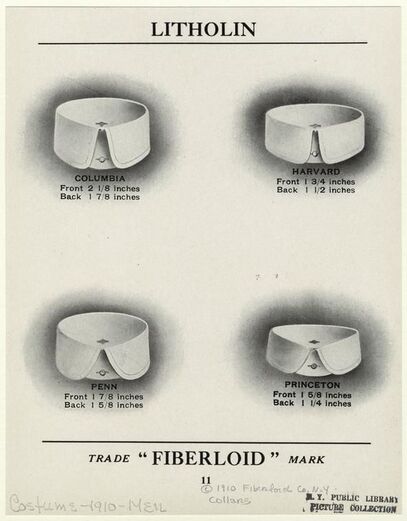

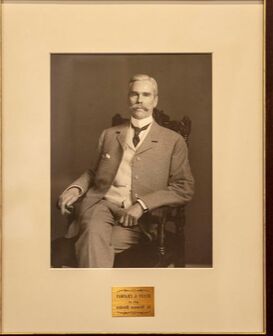

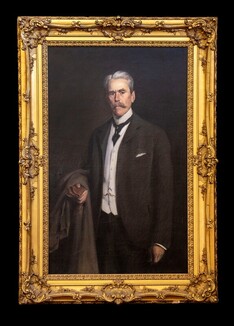

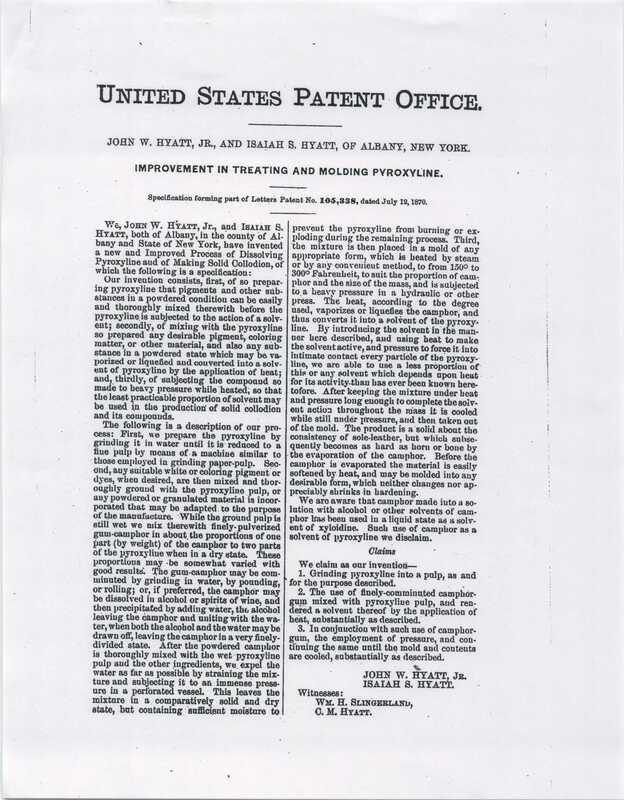

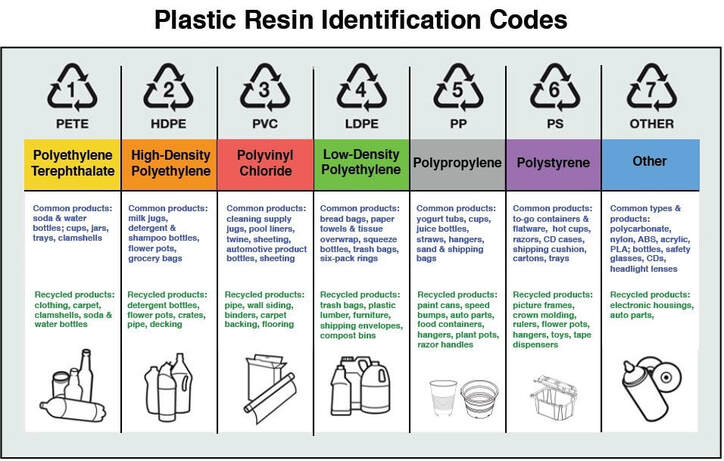

No discussion about plastic can be had without knowledge of how we got here. It begins with ivory. Its historical source is rooted in the carnage of killing elephants (mostly), whales, walruses, narwhals, hippopotamuses, and warthogs for their tusks. Ivory was used for piano keys, hair combs, men’s dress collars, dentures, religious items, jewelry and incredibly, billiard balls. Billiards was a huge indoor recreational game in the late 19th century. Ivory billiard ball Ivory’s burgeoning demand gave way to the desire to find a suitable and less expensive substitute. Celluloid was the first commercial response to this need. Henry Stanton Chapman, the Glen Ridge Library’s original benefactor, made his fortune in celluloid manufacturing. He owned and operated the Arlington Company in Arlington, NJ, which is a neighborhood in Kearny. He sold it to DuPont circa 1914. He then went on to manage his investments and engage in local philanthropic endeavors in Glen Ridge. His $50,000 donation provided the funds to build our library, which opened to the public in May 1918. Celluloid’s popularity began to wane toward the middle of the 20th century, following the introduction of plastics based on entirely synthetic polymers created from petroleum. The word “plastic” come from the Greek word "plastikos," which means “capable of being shaped or molded.” 1907 - Bakelite is invented. 1939 - Nylon is launched. 1941 - PET (polyethylene terephthalate) is first produced. PET is now used to make plastic bottles. 1939 to 1945 - Plastics are in high demand during World War ll when plastics were molded and used for cockpits, and nylon for parachutes to hand grenades. 1950s - The first polyethylene bags appear. High-density polyethylene was developed, which made plastic bottles cheaper to manufacture and buy. Single-use plastics are ushered in. 1960s - Plastics are further toughened and refined, allowing them to compete with metals. Plastic inspired the iconic scene from “The Graduate” when Los Angeles businessman Mr. McGuire takes Dustin Hoffman’s character Benjamin Braddock aside and declares, “I just want to say one word to you just one word. Plastic.” Turns out, Mr. McGuire’s advice was prophetic. Here's the clip https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSxihhBzCj Plastic is durable, lightweight and malleable. This is both good news and bad news. Let’s start with good news: The advent of plastic revolutionized modern medicine. Laborious medical equipment sterilization yielded to the use of plastic IV bags, syringes, gloves, masks, bed pans, bandages and prosthetics. Plastic transformed blood-bank collection and storage, too. The bad news: Plastic is durable, lightweight, malleable and made from petroleum. The trouble started when plastic went from being a valuable material to something we were overusing and over-producing without a thought for what would happen when we threw it away. In post-WW ll America, plastic manufacturers shifted their attention and their advertising from military production to consumer items, many of which were single-use and disposable. Fast-forward to today: Single-use plastics are everywhere on land and in our oceans. It’s remarkable to think that a quest for an ivory replacement for billiard balls would lead us to where we are today. We live with plastics, and it lives within us. Plastics changed the essential texture of contemporary life; so, too, has it altered the basic chemistry of our bodies. It leeches into our bodies from plastics we use for food and liquid storage. Fish ingest it when they eat plastic objects, which they mistake for food then we eat the fish. And microplastics are endemic to our oceans. Microplastics are fragments of any type of plastic less than 5 mm in length, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the European Chemicals Agency. Microplastics are found in upcycled clothing and other items made from plastics. It’s in our air when plastic is incinerated and releases gases into the atmosphere. Plastic has morphed from an engineering triumph into a global plague – a double-edged sword with consequences both positive and negative. We need to wield our swords, and sharpen our senses and strengths to combat and challenge our unwieldy use of non-essential single-use plastics while diligently working to discover, or invent alternative inert and non-toxic substances that replicate the positive properties of plastics which have revolutionized our world. Perhaps, a global competition could accelerate this mission, just as a $10,000 prize offered by the Albany Billiard Ball Co., manufacturer in the 1800s ignited the creation of celluloid by John Hyatt Jr. in 1868, followed by an improved patent with his brother, Isaiah S. Haytt in 1870 which evolved into the plethora of plastics were know today. Learn MoreJulie, Beer. Kids vs plastic: ditch the straw and find the pollution solution to bottles, bags, and other single-use plastics. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2020. French, Jess. What a waste: trash, recycling, and protecting our planet. New York, NY:, DK Publishing, 2019. Plastic soup Foundation https://www.plasticsoupfoundation.org/en/

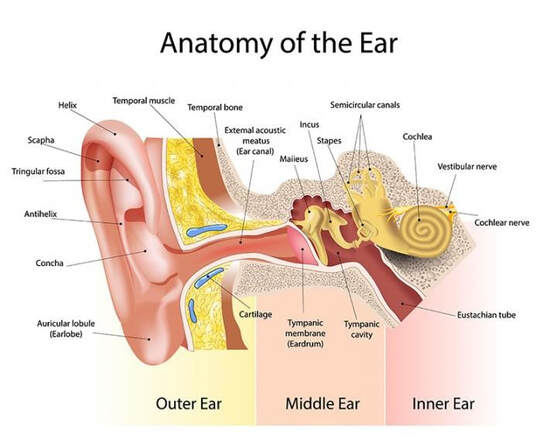

Recently while waiting for a bus, my ears were assaulted simultaneously by the sounds of construction equipment, sirens, car horns and the whiz of traffic. My ears hurt. Yet, when I saw two sparrows pecking on the sidewalk for food, I noticed that they seemed oblivious to all the noise. I thought to myself, “How could such small creatures (a sparrow weighs approximately 0.85 – 1.4 ounces) with ears that are tiny holes on the side of their heads covered with feathers, withstand such a high frequency of noise. I then thought, “Is it possible that these birds are deaf?” I discovered that I’m not the only one intrigued by birds and their hearing. Stanford University scientists are actively studying why birds never go totally deaf yet we humans do. Their research is showing that birds can regrow damaged hair cells in their inner ears - an amazing anatomical feat. So where exactly are these hair cells located and how do they work? First, let's look at the anatomy of the human ear. The ear is made up of three parts: the outer ear, the middle ear and the inner ear. These microscopic hair cells, which birds can regrow, are located in the cochlea of the inner ear. The cochlea is shaped like a small snail and is about the size of a pea. It is fluid-filled and lined with these tiny hairs (there are about 15,000 in the human ear) Vibrations are transmitted as waves from the outer ear to the eardrum. The eardrum passes the vibrations along through three tiny bones, the malleus, incus and stapes. They pass vibrations to the cochlea. The vibrations pass through the cochlea fluid and over the tiny hair cells in a wave-like motion creating electrical signals which are sent to the brain via the via the cochlea nerve. At the end of this process, we are able to hear the sounds created by the initial vibrations from our outer ear. Healthy hair cells can be likened to wheat standing tall in a field. In humans, these tiny hair cells die for various reasons: injuries, aging and loud noises. Dead hair cells look like a wheat field pelted by heavy rain which don’t grow back in humans. Scientists are working to unravel this mystery of how birds can regenerate cochlear hair cells. And the discovery and identification of gene mutations related to cochlea hair cell degeneration, offers another avenue to pursue in their quest to find a way to regenerate healthy hair cells. If, and when they do, it holds out the promise that one day we could be like our feathered friends and never go permanently deaf. I hope this post gives you a renewed appreciation of the sense of hearing, how our ears work and the wonder of birds. Spiro, Ruth. Baby loves the five senses: hearing! Watertown, MA, Charlesbridge, 2019. Sibley, David. Sibley guide to birds. 2nd ed., New York, Knopf, 2014 . |

Curiosity Corner writer & contributor:Helen Beckert, Reference Librarian at the Glen Ridge Public Library Archives

June 2023

Categories |

|

Glen Ridge Public Library

240 Ridgewood Avenue Glen Ridge, NJ 07028 Phone: 973-748-5482 Email: [email protected] © 2024 Glen Ridge Public Library Site last updated July 15, 2024 |

LIBRARY HOURS Monday 9 am - 8 pm Tuesday 9 am - 8 pm Wednesday 9 am - 8 pm Thursday 9 am - 5 pm Friday 9 am - 5 pm Saturday 9 am - 5 pm Sunday CLOSED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed